[ad_1]

The Netzarim Corridor is a four-mile-long road just south of Gaza City that runs from east to west, stretching from the Israeli border to the Mediterranean Sea. Hamas has made Israel’s withdrawal from the area a central demand in cease-fire negotiations.

But even as talks have continued over the past two months, Israeli forces have been digging in. Three forward operating bases have been established in the corridor since March, satellite imagery examined by The Washington Post shows, providing clues about Israel’s plans. At the sea, the road meets a new, seven-acre unloading point for a floating pier, an American project to bring more aid into Gaza.

Israel insists it does not intend to permanently reoccupy Gaza, which its troops controlled for 38 years until withdrawing in 2005. But the construction of roads, outposts and buffer zones in recent months points to an expanding role for Israel’s military as alternative visions for postwar Gaza falter.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has released few concrete plans for the “day after” — a source of frustration for his generals and for Washington — but has repeatedly vowed to maintain “indefinite” security control over the enclave. In addition to conducting future raids from outside, Israeli troops may need to “be inside” Gaza to ensure the demilitarization of Hamas, Netanyahu said in a podcast interview earlier this week.

In addition to leverage in negotiations, control of the corridor gives the Israeli military valuable flexibility, allowing troops to be deployed quickly throughout the enclave. It also affords the Israel Defense Forces the ability to maintain control over the flow of aid and the movement of displaced Palestinians, which it says is necessary to prevent Hamas fighters from regrouping.

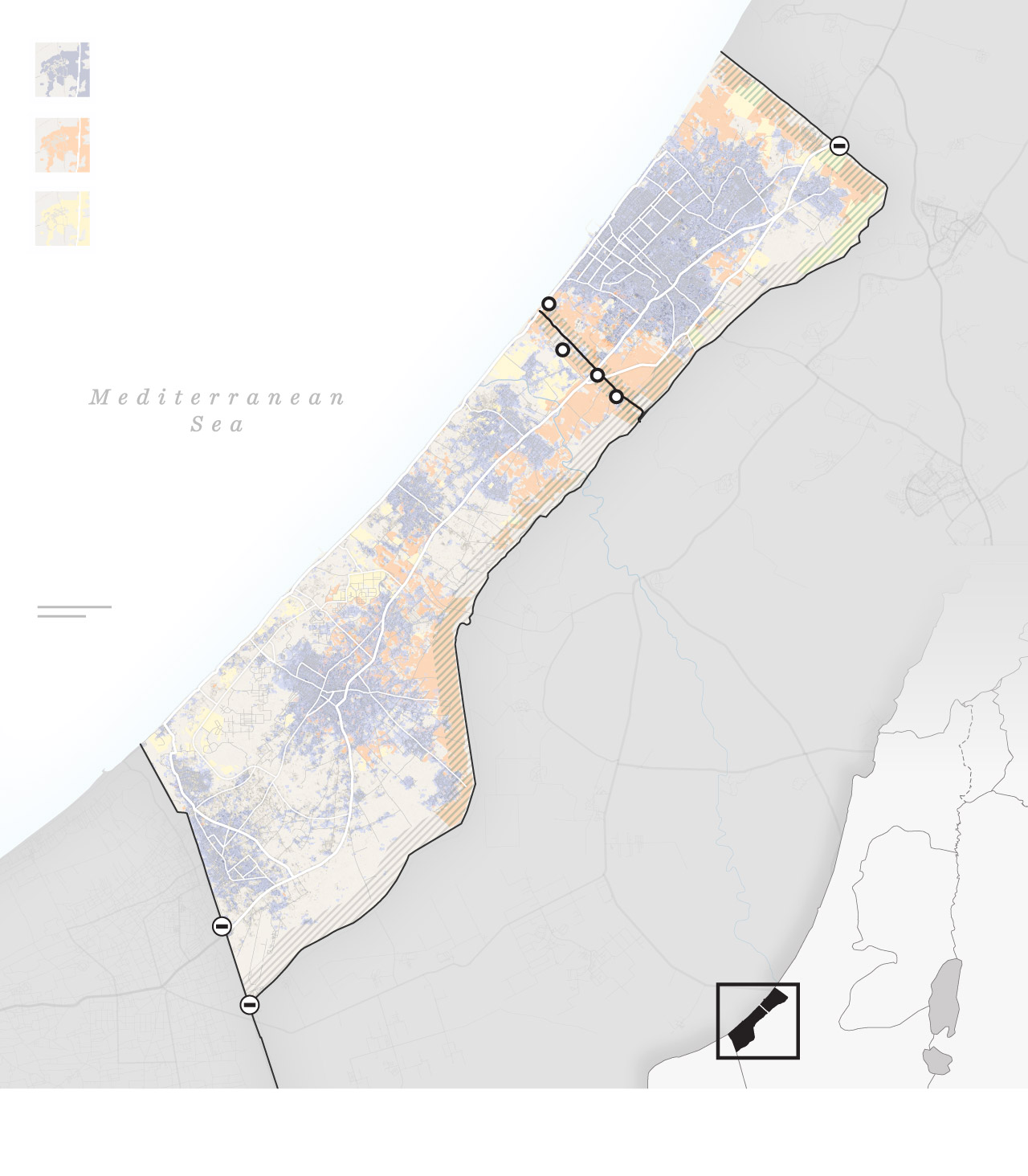

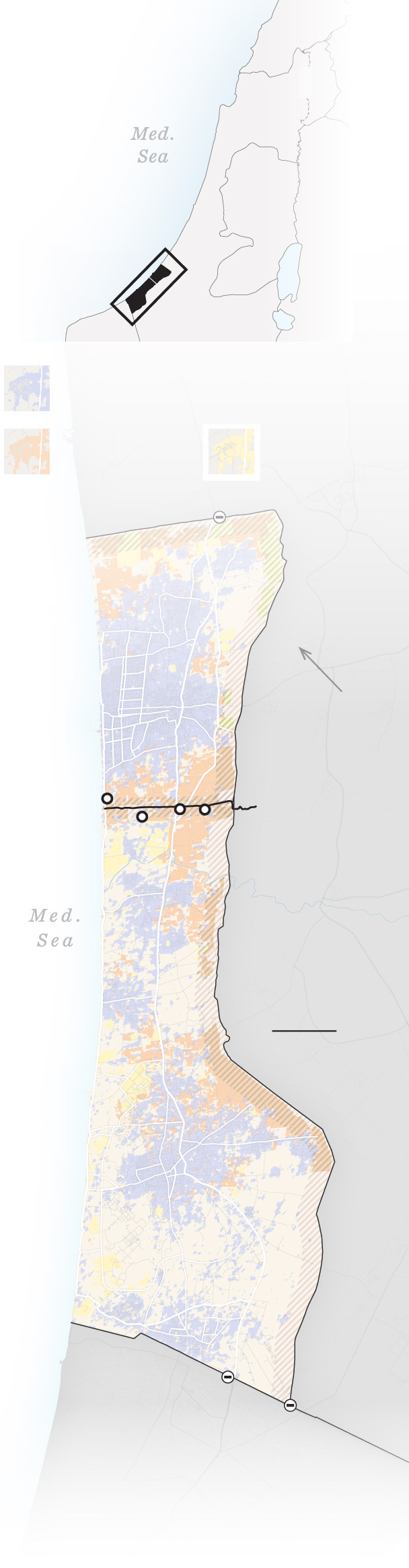

At least 750 buildings have been destroyed in what appears to be a systematic effort to create a “buffer zone” that stretches at least 500 yards on either side of the road, according to an analysis by Hebrew University’s Adi Ben-Nun, a geographic data specialist. Another 250 buildings have been razed in the area of the U.S. pier, he said.

The IDF declined to comment on the clearing of buildings around the corridor, saying it could not answer operational questions during an ongoing war.

Military experts say it is part of a large-scale, long-term reshaping of Gaza’s geography, harking back to past Israeli plans to carve Gaza into easier-to-control cantons.

Damaged or destroyed buildings

detected by satellite

Destroyed

agricultural land

Partially damaged

agricultural land

New Israeli road

and outposts

Sources: Building analysis of Copernicus Sentinel-1 satellite data through May 8 by Corey Scher of CUNY Graduate

Center and Jamon Van Den Hoek of Oregon State University, Microsoft Maps. Agriculture analysis

by Adi Ben-Nun of Hebrew University.

Damaged or destroyed buildings

detected by satellite

Partially damaged

agricultural land

Destroyed

agricultural land

New Israeli

road and

outposts

Sources: Building analysis of Copernicus Sentinel-1 satellite data

through May 8 by Corey Scher of CUNY Graduate Center and Jamon

Van Den Hoek of Oregon State University, Microsoft Maps.

Agriculture analysis by Adi Ben-Nun of Hebrew University.

Damaged or destroyed buildings

detected by satellite

Partially damaged

agricultural land

Destroyed

agricultural land

New Israeli

road and

outposts

Sources: Building analysis of Copernicus Sentinel-1

satellite data through May 8 by Corey Scher of CUNY

Graduate Center and Jamon Van Den Hoek of Oregon

State University, Microsoft Maps. Agriculture analysis

by Adi Ben-Nun of Hebrew University.

“What we need is full freedom of operation for the IDF everywhere in Gaza,” said Amir Avivi, a reserve brigadier general and former deputy commander of the Israel Defense Forces’ Gaza Division.

‘Welcome to Netzarim Base’

The Netzarim Corridor is named after an Israeli settlement that used to sit on the coastal route — the second “finger” of then-Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s “five fingers” strategy that envisioned carving Gaza into segments, all under Israeli security control. The plan was only partially implemented before Sharon — once a champion of settlements — ordered an Israeli withdrawal from Gaza in 2005.

“It’s no surprise that Israel went back and established this as a new corridor,” said Lt. Col. Jonathan Conricus, a fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies and a former IDF spokesman. “The terrain is the most conducive there and it suits the military purposes.”

The Netzarim axis was among the first targets for Israeli troops after they invaded Gaza in response to the Hamas-led attack on Oct. 7, pushing forward to cleave the Strip in two.

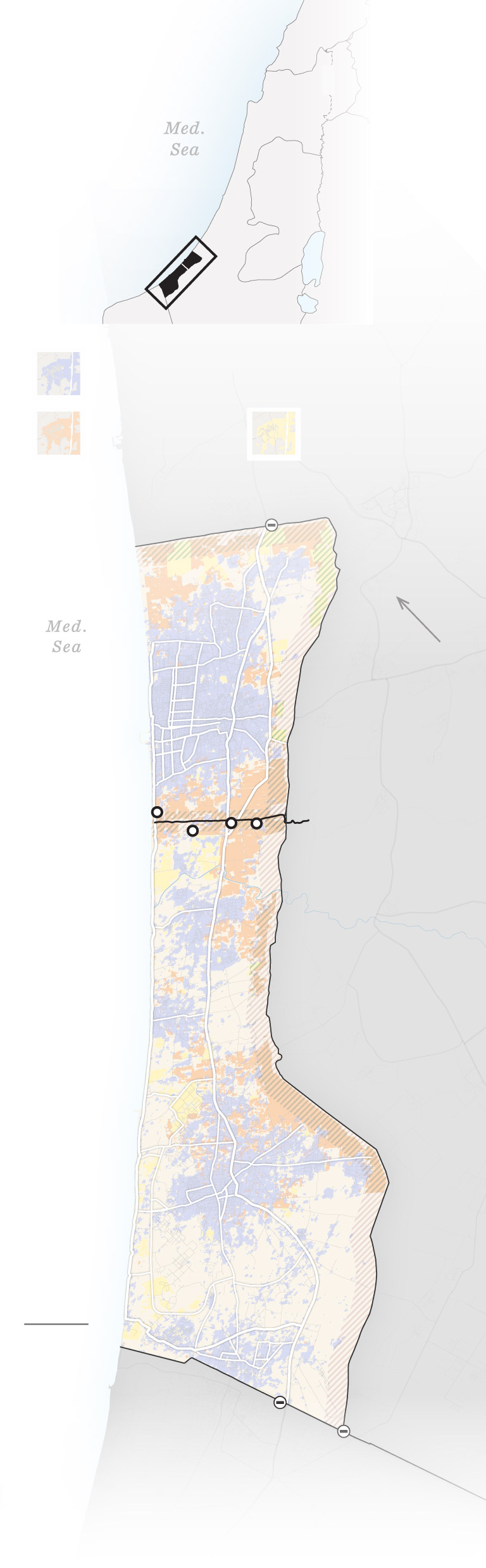

By Nov. 6, troops had cut an informal, winding track to the sea that allowed armored vehicles to reach al-Rashid Road, a major north-south thoroughfare that runs along Gaza’s coast. In February and March, Israeli troops formalized the corridor by building a straight road a few hundred meters to the south. The last section of the road, nearest to the coast, was completed between March 5 and March 9, satellite imagery shows.

The IDF says the road enables military vehicles to travel from one side of the Strip to the other in just seven minutes, giving soldiers speedy and unimpeded access to north and central Gaza. It was used as a base of operations for recent IDF attacks in Zeitoun, in northern Gaza, said one Israeli military official, speaking on the condition of anonymity in line with IDF protocol.

IDF’s infrastructure along the Netzarim Corridor

Work starts being

visible in satellite

images around

mid March

Section built

between Feb. 14

and March 9

Earth berm created

close to the corridor

during the second

half of March

A road from the main corridor

to the Turkish hospital

compound was also created

in late March.

Turkish-Palestinian

Friendship Hospital

Pre existing,

paved section

Possible

temporary

buildings

Work starts being

visible in sat. images

between March 5

and March 15

Section built

between Feb. 7 and

Feb. 14

Section built

between Feb. 14 and

March 9

Work starts being

visible in satellite

images between

March 15

and March 30

Source: Satellite image as captured on April 16, Planet Labs

IDF’s infrastructure along the Netzarim Corridor

Work starts being visible

in satellite images

around mid March

Section built

between Feb. 14

and March 9

Earth berm created

close to the corridor

during the second

half of March

A road from the main corridor

to the Turkish hospital

compound was also created

in late March.

Turkish-Palestinian

Friendship Hospital

Pre existing,

paved section

Possible

temporary

buildings

Work starts being

visible in sat. images

between March 5

and March 15

Section built

between Feb. 7 and

Feb. 14

Section built

between Feb. 14 and

March 9

Work starts being

visible in satellite images

between March 15

and March 30

Source: Satellite image as captured on April 16, Planet Labs

IDF’s infrastructure along the Netzarim Corridor

Work starts being visible

in satellite images around

mid March

Road visible

in satellite

image since

November 2023

Section built

between Feb. 14

and March 9

Earth berm created

close to the corridor

during the second

half of March

Wastewater

treatment

plant

A road from the main corridor

to the Turkish hospital

compound was also created

in late March.

Turkish-Palestinian

Friendship Hospital

Destroyed building

of the al-Riyadh

auditorium

Preexisting,

paved section

Work starts being visible in

satellite images between

March 5 and March 15

Possible

temporary

buildings

Section built

between Feb. 7 and

Feb. 14

Road visible in satellite

image since November

2023

Section built

between Feb. 14 and

March 9

Work starts being visible

in satellite images between

March 15 and March 30

Source: Satellite image as captured on April 16, Planet Labs

IDF’s infrastructure along the Netzarim Corridor

Work starts being visible

in satellite images around

mid March

Section built

between Feb. 14

and March 9

Road visible in satellite

image since November

2023

Earth berm created

close to the corridor

during the second

half of March

Wastewater

treatment

plant

A road from the main corridor

to the Turkish hospital

compound was also created

in late March.

Turkish-Palestinian

Friendship

Hospital

Areas likely used

as staging ground

by the IDF in 2023

Destroyed building

of the al-Riyadh

auditorium

Preexisting,

paved section

Work starts being visible

in satellite images between

March 5 and March 15

Possible

temporary

buildings

Section built

between Feb. 7 and

Feb. 14

Road visible in satellite

image since November

2023

Section built

between

Feb. 14 and

March 9

Work starts being visible in satellite

images between March 15 and March 30

Source: Satellite image as captured on April 16, Planet Labs

The corridor bisects Gaza’s only two major north-south roads — Salah al-Din Road, in the middle of the territory, and al-Rashid Road along the coast. The IDF began building forward operating bases at both points in early March.

The bases offer signs that the IDF could be preparing at some point for a controlled return of civilians to the north. Next to both bases, on roads leading north, are structures that appear to be “long parallel intake hallways” leading to a central compound, said Sean O’Connor, a lead analyst for satellite imagery at the security firm Janes.

The United States has said that Gazans who fled to Rafah and other points south should be allowed to return to their homes in the north; United Nations experts have said blocking them could amount to the “forcible transfer” of the population, a crime against humanity.

Jumaa Abu Hasira, 37, said soldiers fired shots in the air as he approached the corridor last month during a lull in the fighting, when rumors swirled that families could go north again. He was then detained, he said — blindfolded, hit with a rifle butt, beaten and interrogated for eight hours.

The IDF acknowledged that soldiers used “cautionary fire” as Gazans, including “armed terrorists,” approached the corridor, but did not respond to questions about Abu Hasira’s alleged detention.

The al-Rashid outpost also features observation points and a possible sentry post, said William Goodhind, an open-source researcher with Contested Ground, a research project that tracks military movements in satellite imagery.

The forward operating base on al-Rashid Road sits next to a jetty constructed in mid-March to receive aid for distribution by the World Central Kitchen charity. The U.S. floating pier is expected to be in the same area, with IDF troops providing security for shipments by sea.

“Welcome to Netzarim Base,” reads the blue graffiti on the concrete barriers outside, according to a photo geolocated by The Post and posted on X by an Israeli journalist who said it was spray painted by his brother. At night, bright white flood lights are visible for miles around.

“It is the only place in Gaza that is lit,” said one 29-year-old woman who lives just south of the base, speaking by phone on the condition of anonymity out of fear for her safety. “They usually go to an area and leave afterward,” she said of Israeli troops, adding that in Netzarim they look set to stay.

The fact that the pier lands at the end of the Israeli-military controlled corridor “suggests the IDF wants to be to control the flow of aid,” said Michael Horowitz, head of intelligence at Le Beck International. The corridor also links up with “Gate 96,” a new access point on Israel’s border with central Gaza that has recently been opened for aid trucks, according to the military official.

“You’re waiting for three to four hours, you can be sent back, you can be arrested,” Mohammed Abu Mughaisib, deputy medical coordinator for Doctors Without Borders, said of aid trucks trying to traverse the corridor.

The United Nations has said that Israel’s repeated refusal to allow humanitarian convoys access to the north has magnified the hunger crisis there — described by the head of the World Food Program as a “full-blown famine.”

IDF’s al-Rashid outpost

According to experts, a series of long “halls” could be intake areas, leading

to possible holding areas.

Masts

for operational

communication

Masts for operational

communications

Source: Planet Labs and IDF handout images

IDF’s al-Rashid outpost

According to experts, a series of long “halls” could be intake areas, leading to possible holding areas.

Masts for

operational

communication

Masts for operational

communications

Source: Planet Labs and IDF handout images

IDF’s al-Rashid outpost

According to experts, a series of long “halls” could be intake areas, leading to possible holding areas.

Masts

for operational

communication

Masts for operational

communications

Source: Planet Labs and IDF handout images

IDF’s al-Rashid outpost

According to experts,

a series of long “halls” could be intake areas, leading to possible holding areas.

Masts

for operational

communication

Masts for operational

communications

Source: Planet Labs and IDF handout images

Radar and observation capabilities have been installed at the new outposts, said Doron Kadosh, a military reporter with Israel’s army-run radio station who visited the Salah al-Din outpost last month. His photos show blue and white portable toilets, generators and towering red and white communications towers.

“There was nothing,” he said of his first visit along the corridor in October, when it was still just a tank track. Now bases have sleeping areas, showers, a portable canteen building and hard cover shelters, Kadosh said.

Israeli troops also appear to have commandeered nearby civilian structures and turned them into military outposts. One is a former school in the village of Juhor ad Dik, about a mile from the border with Israel. Protective sand berms appeared at the location between March 15 and March 30, according to satellite imagery. The rest of the village has been destroyed.

Abdel Nasser, 45, fled his farm house in Juhor ad Dik with his wife and five children in October. “It used to be a haven for my family and me … where we spent countless beautiful moments together,” he said.

“About two weeks ago, my neighbors informed me that the entire area had been destroyed, and all the surrounding agricultural land had been bulldozed.” He hasn’t been able to bring himself to tell his wife yet.

Israeli troops also appear to be using the Turkish-Palestinian Friendship Hospital, which once specialized in treatment for cancer patients, as a base of operations. The hospital shut down in the first week of November due to nearby airstrikes and lack of fuel, and thousands of cancer patients have been left without care. Sand berms appeared around the hospital in late November.

An Israeli soldier filmed himself tearing down large parts of the hospital with an earth mover in February. Images published online on May 8 by the Palestinian journalist Younis Tirawi and geolocated by The Post show Israeli soldiers using the hospital as a sniper position.

By March, Israeli forces had cleared hundreds of acres around the hospital — demolishing greenhouses and blowing up Israa University and the Palace of Justice, which housed Gaza’s high courts.

“Israel has not provided cogent reasons for such extensive destruction of civilian infrastructure,” Volker Türk, the U.N. high commissioner for human rights, said in February.

In all, the area cleared around the corridor and the pier encompasses at least four square miles, or a little more than 2,500 acres, according to the analysis by Ben-Nun from Hebrew University, though extensive damage to buildings and agricultural land extends farther.

“Everything is demolished along the way,” he said. “Completely demolished.”

Israel has indicated it may be willing to pull out of the corridor in the short term. The cease-fire deal that Hamas agreed to last week sets out a staggered drawdown from the area, according to a copy of the document obtained by The Post and verified by a person close to the negotiations.

On the 22nd day, the IDF must withdraw entirely from the Netzarim Corridor area and “completely dismantle military sites and installations,” it says.

But the IDF is likely to have been given assurances that it could return to Netzarim, even if it were forced to leave for a few months during a cease-fire, Horowitz said. The construction of multiple outposts, roads and extensive clearing “would suggest this might become permanent,” he said.

A protracted period of military occupation appears increasingly likely, military analysts say, in the absence of other plans for governance in postwar Gaza. Israel has pushed back against a U.S. proposal for a return of the Palestinian Authority, and there appears to be little regional buy-in for Arab security forces.

A long-term Israeli troop presence would be deeply unpopular in Gaza, with the corridor already a lightning rod for attacks. Hamas and other militant groups, including Palestinian Islamic Jihad and al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades, have launched more than half a dozen rocket and mortar attacks on Israeli troops in the corridor in the last week.

But as Hamas returns to northern areas already cleared by the IDF, military occupation — once an unthinkable suggestion within Israel — is now being openly discussed.

“There is no other option,” said Michael Milshtein, former adviser on Palestinian affairs to the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories.

Hajar Harb in London, Heba Farouk Mahfouz in Cairo, Karen DeYoung in Washington, Jarrett Ley in New York, Laris Karklis in Washington and Júlia Ledur in Philadelphia contributed to this report.

[ad_2]

Source link