[ad_1]

At St. Petersburg State University, this meant dismantling a prestigious humanities program called the Faculty of Liberal Arts and Sciences. For more than a decade, until May 2022, the faculty — or college — was led by Alexei Kudrin, a liberal economist and former finance minister who had been a close associate of Putin’s since the early 1990s, when they were deputy mayors together in St. Petersburg.

“We had many classes on U.S. history, American political life, democracy and political thought, as well as courses on Russian history and political science, history of U.S.-Russian relations, and even a course titled ‘The ABCs of War: Causes, Effects, Consequences,’” said a student at the faculty, also known as Smolny College. “They are all gone now,” the student said, speaking on the condition of anonymity for fear of retribution.

In a radical reshaping of Russia’s education system, curriculums are being redrawn to stress patriotism and textbooks rewritten to belittle Ukraine, glorify Russia and whitewash the totalitarian Soviet past. These changes — the most sweeping to schooling in Russia since the 1930s — are a core part of Putin’s effort to harness the war in Ukraine to remaster his country as a regressive, militarized state.

Since the February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, leaders of Russian universities, which are overwhelmingly funded by the state, have zealously adopted the Kremlin’s intolerance of any dissent or self-organization, according to an extensive examination by The Washington Post of events on campuses across Russia, including interviews with students and professors both still in the country and in exile.

Professors who spoke out against the war, or allowed safe spaces for students to question it, have been fired. Students who picketed or posted on social media for peace were expelled.

Meanwhile, those who volunteer to fight in Ukraine have been celebrated in line with Putin’s promises that war heroes and their descendants will become the new Russian elite, with enhanced social benefits, including special preference for children seeking to enter top academic programs. Normally, such programs require near-perfect grades and high scores on competitive exams — uniform standards that applicants from all societal backgrounds have relied on for decades.

And the most fundamental precept of academic life — the freedom to think independently, to challenge conventional assumptions and pursue new, bold ideas — has been eroded by edicts that classrooms become echo chambers of the authoritarian nativism and historical distortions that Putin uses to justify his war and his will.

As a result, a system of higher learning that once was a beacon for students across the developing world is now shutting itself off from peer academies in the West, severing one of the few ties that had survived years of political turbulence. Freedom of thought is being trampled, if not eradicated. Eminent scholars have fled for positions abroad, while others said in interviews that they are planning to do so.

At the Russian State University for the Humanities in Moscow, officials last July created the Ivan Ilyin Higher Political School, which is now being led by Alexander Dugin, a fervent pro-Putin and Orthodox Christian ideologue who was tasked with “revising domestic scientific and educational paradigms and bringing them into line with our traditional Russian spiritual and moral values.”

“There has been a catastrophic degradation in Western humanitarian history,” Dugin said at a January seminar on transforming Russian humanities education. “This is evidenced by gender problems, postmodernism and ultraliberalism. We can study the West, but not as the ultimate universal truth. We need to focus on our own Russian development model.”

Last month, students pushed an online petition to protest the naming of the school after Ilyin, a philosopher who defended Hitler and Mussolini in World War II and advocated for the return of czarist autocracy in Russia. In a statement to Tass, the state-controlled news service, the university denounced the petition as “part of the information war of the West and its supporters against Russia” and asserted, without providing evidence, that the group behind it had no connection to students at the school.

Programs specializing in the liberal arts and sciences are primary targets because they are viewed as breeding grounds for dissent. Major universities have cut the hours spent studying Western governments, human rights and international law, and even the English language.

“We were destroyed,” said Denis Skopin, a philosophy professor at Smolny College who was fired for criticizing the war. “Because the last thing people who run universities need are unreliable actors who do the ‘wrong’ thing, think in a different way, and teach their students to do the same.”

The demise of

Smolny College

The demise of

Smolny College

The demise of Smolny College

The demise of Smolny College

St. Petersburg State University, commonly known as SPbU, has long been one of Russia’s premier academies of higher learning. It is the alma mater of both Putin, who graduated with a degree in law in 1975, and former president Dmitry Medvedev, who received his law degree 12 years later and now routinely threatens nuclear strikes on the West as deputy chairman of Russia’s national security council.

In many ways, the university has become the leader in reprisals against students and staff not loyal to the Kremlin, with one newspaper dubbing it the “repressions champion” of Russian education. Its halls have become a microcosm of modern Russia in which conservatives in power are pushing out the few remaining Western-oriented liberals.

Like other aspects of Putin’s remastering of Russia — such as patriotic mandates in the arts and the redrawing of the role of women to focus on childbearing — the shift in education started well before the invasion of Ukraine. In 2021, Russia ended a more than 20-year-old exchange program between Smolny College and Bard College in New York state by designating the private American liberal arts school an “undesirable” organization.

Jonathan Becker, Bard’s vice president for academic affairs and a professor of political studies, said the demise of Smolny was emblematic of a wider shift in Russia as well as a new intolerance of the West.

“A huge number of faculty have been let go, several departments closed, core liberal arts programs which focus on critical thinking have been eliminated,” Becker said. “All of that has happened, and it’s not just happened at Smolny — it has happened elsewhere. But we were doubly problematic because we both represent critical thinking and partnership with the West. And neither of those are acceptable in present-day Russia.”

In October 2022, in a scene captured on video and posted on social media, dozens of students gathered in a courtyard to bid a tearful goodbye to Skopin, Smolny’s cherished philosophy professor who was fired for an “immoral act” — protesting Putin’s announcement of a partial military mobilization to replenish his depleted forces in Ukraine.

The month before, according to court records and interviews, Skopin was arrested at an antiwar rally. He ended up sharing a jail cell with another professor, Artem Kalmykov, a young mathematician who had recently finished his PhD at the University of Zurich.

That fall, the university launched an overhaul that all but shut Smolny College and replaced the curriculum with a thoroughly revamped arts and humanities program.

The dismantling of Smolny marked the resolution of a years-long feud between Kudrin, the liberal-economist dean, and Nikolai Kropachev, the university rector, whom tutors and students described as a volatile character with a passion for building ties in the highest echelons of the government.

It’s hard to describe the insane level of anxiety the students felt at the start of the invasion, and I’d say 99 percent of them were against it.”

Denis Skopin

Former philosophy professor at Smolny College

It’s hard to describe the insane level of anxiety the students felt at the start of the invasion, and I’d say

99 percent of them were against it.”

Denis Skopin

Former philosophy professor at Smolny College

It’s hard to describe the insane level

of anxiety the students felt at the start

of the invasion, and I’d say 99 percent

of them were against it.”

Denis Skopin

Former philosophy professor at Smolny College

It’s hard to describe the insane level of anxiety

the students felt at the start of the invasion,

and I’d say 99 percent of them were against it.”

Denis Skopin

Former philosophy professor at Smolny College

In February, Sergei Naryshkin, the head of Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service, sent a heartfelt birthday message to Kropachev, thanking him for his “civic and political activity” and for “comprehensive assistance in replenishing personnel.”

One student described how Kropachev once interrupted a meeting with students and hinted that he needed to take a call from Putin, in what the student viewed as a boast of his direct access to the Russian leader. Both St. Petersburg State University and Moscow State University were assigned a special status in 2009, under which their rectors are appointed personally by the president.

Skopin, who earned his PhD in France, and his cellmate, Kalmykov, were perfect examples of the type of academic that Russia aspired to attract from the early 2000s to the mid-2010s — enticed after studying abroad to bring knowledge home amid booming investment in higher education. But by 2022, the system seemed to have no need for them.

Video of the gathering in the courtyard shows students erupting in sustained applause, and one student coming forward to hug Skopin.

“It’s hard to describe the insane level of anxiety the students felt at the start of the invasion, and I’d say 99 percent of them were against it,” Skopin said.

After his dismissal, some students tried to fight the administration’s plan to dismantle the Smolny program.

“At one point we found ourselves in a situation where out of 30 original faculty staff, we had just three tutors left,” said Polina Ulanovskaya, a sociology student and activist who led the student union. “And the quality of education definitely suffered, especially all of the politics-related classes.”

Ulanovskaya said that on the political science track, only two professors have stayed, and many classes were eliminated, including a human rights course. There are now just two courses offered in English, down from 21.

With every new professor, Ulanovskaya said, she felt a need to test the waters. Would the word “gender” trigger them? Could she say something opposition-leaning? What would be a red flag?

Ulanovskaya opted out of writing a thesis on her main research topic — Russian social movements, politicization of workers and historic-preservation activists — out of fear that it would be blacklisted. Instead, she wrote about Uruguay.

“The main problem at the faculty now is that there is no freedom and especially no sense of security,” she said. “I guess there is no such thing anywhere in Russia now … you can’t trust anyone in any university.”

A few weeks after The Post interviewed Ulanovskaya last fall, she was expelled, formally for failing an exam, but she and Skopin said they believe it was retaliation for her activism.

Another student, Yelizaveta Antonova, was supposed to get her bachelor’s degree in journalism just days after legendary Novaya Gazeta newspaper reporter Yelena Milashina was brutally beaten in Chechnya, the small Muslim-majority republic in southern Russia under the dictatorial rule of Ramzan Kadyrov.

Antonova, who interned at Novaya Gazeta and looked up to Milashina, felt she could not accept her diploma without showing support for her colleague. She and a roommate printed a photo of Milashina, depicting the reporter’s shaved head and bandaged hands, to stage a demonstration at their graduation ceremony — much to the dismay of other classmates, who sought to block the protest.

“They essentially prevented us from going on stage,” Antonova said. “So we did it outside of the law school, and we felt it was extra symbolic because Putin and Medvedev studied in these halls.”

They held up the poster for about half an hour, until another student threatened them by saying riot police were on the way to arrest them. Antonova believes the protest cost her a spot in graduate school, where she hoped to continue her research comparing Russia’s media landscape before and after the invasion.

Eight months after the graduation ceremony, authorities launched a case against Antonova and her roommate for staging an unauthorized demonstration — an administrative offense that is punishable by a fine and puts people on law enforcement’s radar. Antonova left the country to continue her studies abroad.

The history college at St. Petersburg State has long been a battleground for various ideologies, with cliques ranging from conservatives and Kremlin loyalists to unyielding opposition-minded liberals, according to interviews with students and professors.

The February 2022 invasion of Ukraine caused a deeper split. Some students and professors openly praised Putin’s “special military operation,” as the Kremlin called the war, while others joined rallies against it.

“The war gave them carte blanche,” said Michael Martin, 22, a former star at the college — to which he was automatically admitted after winning two nationwide academic competitions and where he earned straight A’s.

Martin was a leader of the student council, which on the day of the invasion issued an antiwar manifesto quickly drafted in a cafe.

Another history student, Fedor Solomonov, took the opposite view and praised the special military operation on social media. When Solomonov was called up as part of the mobilization, he declined to take a student deferral and went to fight. He died on the front on April 1, 2023.

Soon after Solomonov’s death, screenshots from internal chats where students often debated history and politics were leaked and went viral on pro-war Telegram channels. In some, Martin and other classmates expressed antiwar sentiments, while another showed a message — allegedly written by an assistant professor, Mikhail Belousov — vaguely describing events in Ukraine as “Rashism,” a wordplay combining “Russia” and “fascism.”

In an aggressive online campaign, pro-war activists demanded that Belousov, who denied writing the message, be fired and that the antiwar students, whom they labeled “a pro-Ukrainian organized crime group,” be expelled.

“A cell of anti-Russian students led by a Russophobe associate professor is operating at the history faculty,” read posts on Readovka, a radical outlet with 2.5 million followers. “They are rabid liberals who hate their country.” Belousov was dismissed and seven students, including Martin, were accused of desecrating Solomonov’s memory and expelled.

Belousov has gone underground and could not be reached for comment.

“They essentially tried to make me do the Sieg Heil,” Martin said, recalling the expulsion hearing, where he said the committee repeatedly asked leading questions trying to get him to say the war was justified. The committee also asked him repeatedly about Solomonov.

“I said he was for the war and I was against it — we could argue about that,” Martin said. “I didn’t find anything funny or interesting in this — I’m truly sorry for what happened to him, but at the same time, I don’t think that he did something good or great by going to war.”

Martin said that as the war raged on, the university began “glorifying death” and praising alumni who had joined the military.

This narrative also warped the curriculum.

A few weeks into the invasion, the school introduced a class on modern Ukrainian history, with a course description asserted that Ukrainian statehood is based “on a certain mythology.”

They essentially tried to make me do the Sieg Heil.”

Michael Martin

Former student at St. Petersburg State University

They essentially tried to make me do the Sieg Heil.”

Michael Martin

Former student at St. Petersburg State University

They essentially tried to make me do the Sieg Heil.”

Michael Martin

Former student at St. Petersburg State University

They essentially tried to make me do the Sieg Heil.”

Michael Martin

Former student at St. Petersburg State University

Belousov, the former assistant professor, criticized a course titled “The Great Patriotic War: No Statute of Limitations,” taught by an instructor with a degree in library science. The key message of the course is that the Soviet Union had no role in the start of World War II — a denial of Russia’s joint invasion of Poland with Nazi Germany in 1939.

According to a government document reviewed by The Post, Russia’s Higher Education Ministry plans to introduce this course at other universities to ensure the “civic-patriotic and spiritual-moral education of youth,” specifically future lawyers, teachers and historians, and to “correct false ideas.”

“These are obviously propaganda courses that are aimed at turning historians into court apologists,” Martin said.

Martin was expelled days before he was supposed to defend his thesis. He quickly left the country after warnings that he and his classmates could be charged with discrediting the army, a crime punishable by up to 15 years in prison. A criminal case was initiated against Belousov on charges of rehabilitating Nazism.

“This is all very reminiscent of the Stalinist 1930s purges,” Martin said. “The limit of tolerated protest now is to sit silently and say nothing. There is despair at the faculty and a feeling that they have crushed everything.”

To lure more Russian men to fight in Ukraine, the government has promised their families various sweeteners, including cheap mortgages, large life insurance payments and education benefits for their children.

In 2022, Putin approved changes to education laws to grant children of soldiers who fought in Ukraine admissions preferences at Russia’s best universities — schools that normally accept only students with near-perfect exam scores and impressive high school records.

Now, at least 10 percent of all fully funded university spots must be allocated to students eligible for the military preference. Those whose fathers were killed or wounded do not need to pass entry exams.

The new law solidified a previous Putin decree that gave special preferences to soldiers and their children. In the 2023-24 academic year, about 8,500 students were enrolled based on these preferences, government officials said. According to an investigation by the Russian-language outlet Important Stories, nearly 900 students were admitted to 13 top universities through war quotas, with most failing to meet the normal exam score threshold.

In areas of Ukraine captured by Russian forces since February 2022, a different takeover of the education system is underway, with Moscow imposing its curriculum and standards just as it did after invading and illegally annexing Crimea in 2014.

For the 2023-24 academic year, according to the Russian prime minister’s office, more than 5 percent of fully state-financed tuition stipends — roughly 37,000 out of 626,000 — were allocated for students at universities in Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson or Zaporizhzhia, the four occupied or partly occupied areas of Ukraine that Putin has claimed to be annexed.

The relatively large allocation of tuition aid in occupied areas shows how financial assistance and education are central to Putin’s effort to seize lands in southeast Ukraine and absorb its population into Russia in violation of international law.

Deans of several leading Russian universities have made highly publicized trips to occupied Ukraine to urge students there to enroll into Russian schools, part of a multipronged effort to bring residents into Moscow’s orbit.

The Moscow-based Higher School of Economics, once considered Russia’s most liberal university, recently established patronage over universities in Luhansk, with Rector Nikita Anisimov often traveling there.

A few weeks after the invasion started, Moscow abandoned the Bologna Process, a pan-European effort to align higher education standards, as Russia’s deans and rectors strove to show they weren’t susceptible to foreign influence.

Higher Education Minister Valery Falkov said Russian universities would undergo significant changes in the next half-decade, overseen by the national program “Priority 2030,” which envisions curriculums that ensure “formation of a patriotic worldview in young people.”

Soon after Russia quit the Bologna Process, Smolny College was targeted for overhaul.

“The decision was an expected but distinct shift from the more liberal model of Russian higher education policy that emerged after the collapse of the Soviet Union,” said Victoria Pardini, a program associate at the Kennan Institute, a Washington think tank focused on Russia.

Another prestigious school, the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration, canceled its liberal arts program in 2022 after authorities accused it of “destroying national values.”

In mid-October 2023, the Higher Education Ministry ordered universities to avoid open discussion of “negative political, economic and social trends,” according to a publicly disclosed report by British intelligence. “In the longer term, this will likely further the trend of Russian policymaking taking place in an echo-chamber,” the report concluded.

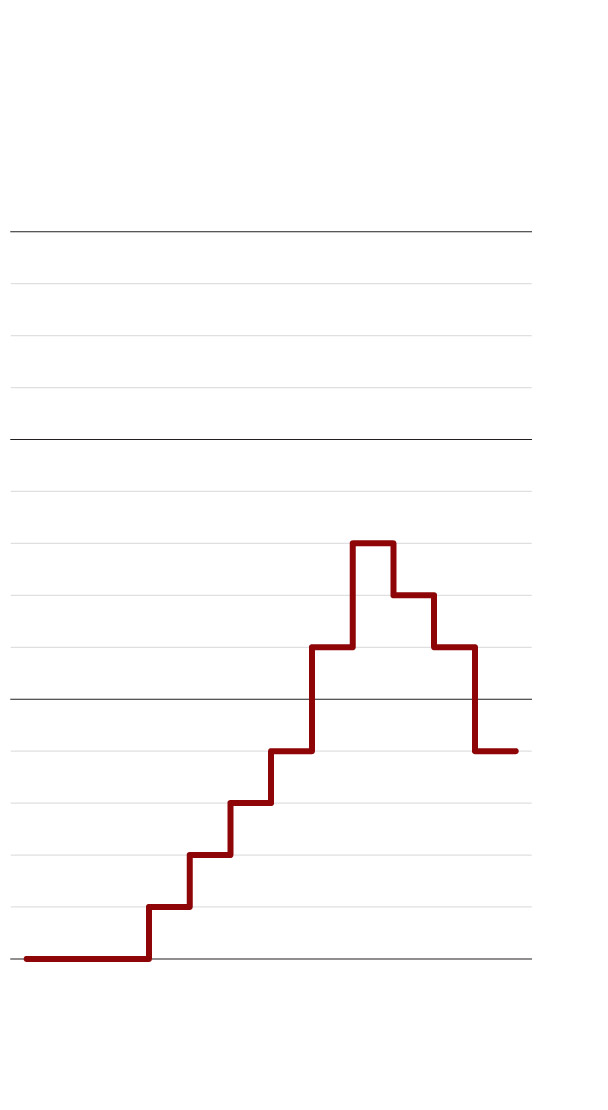

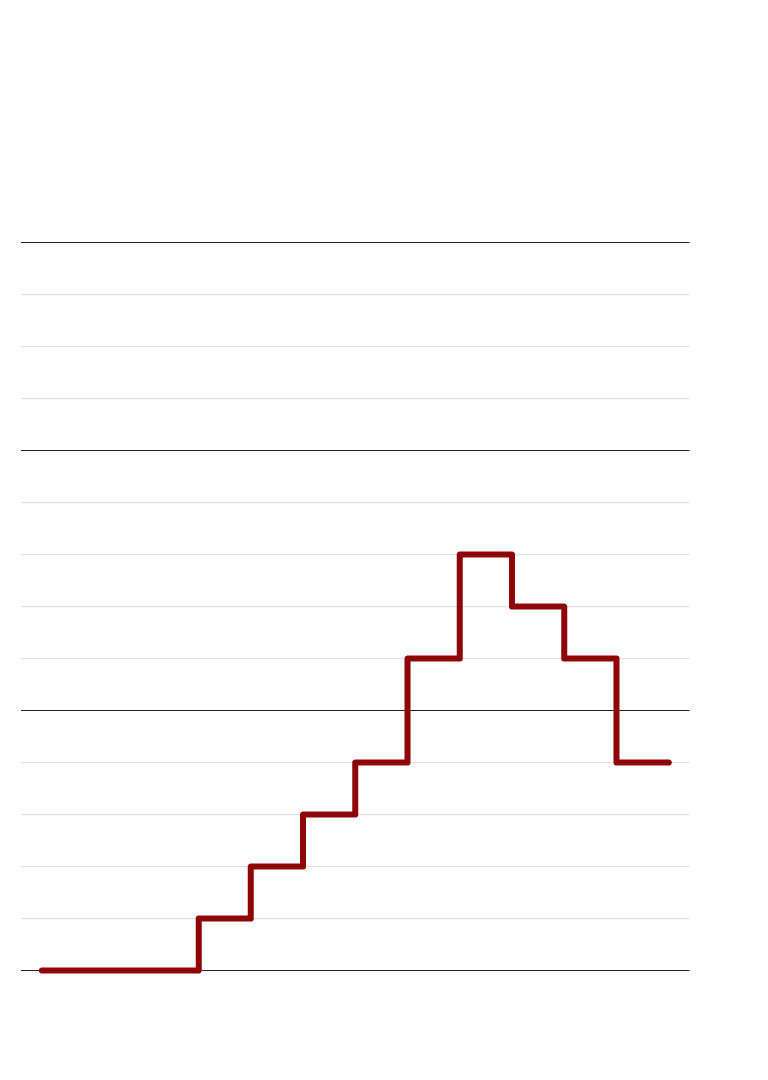

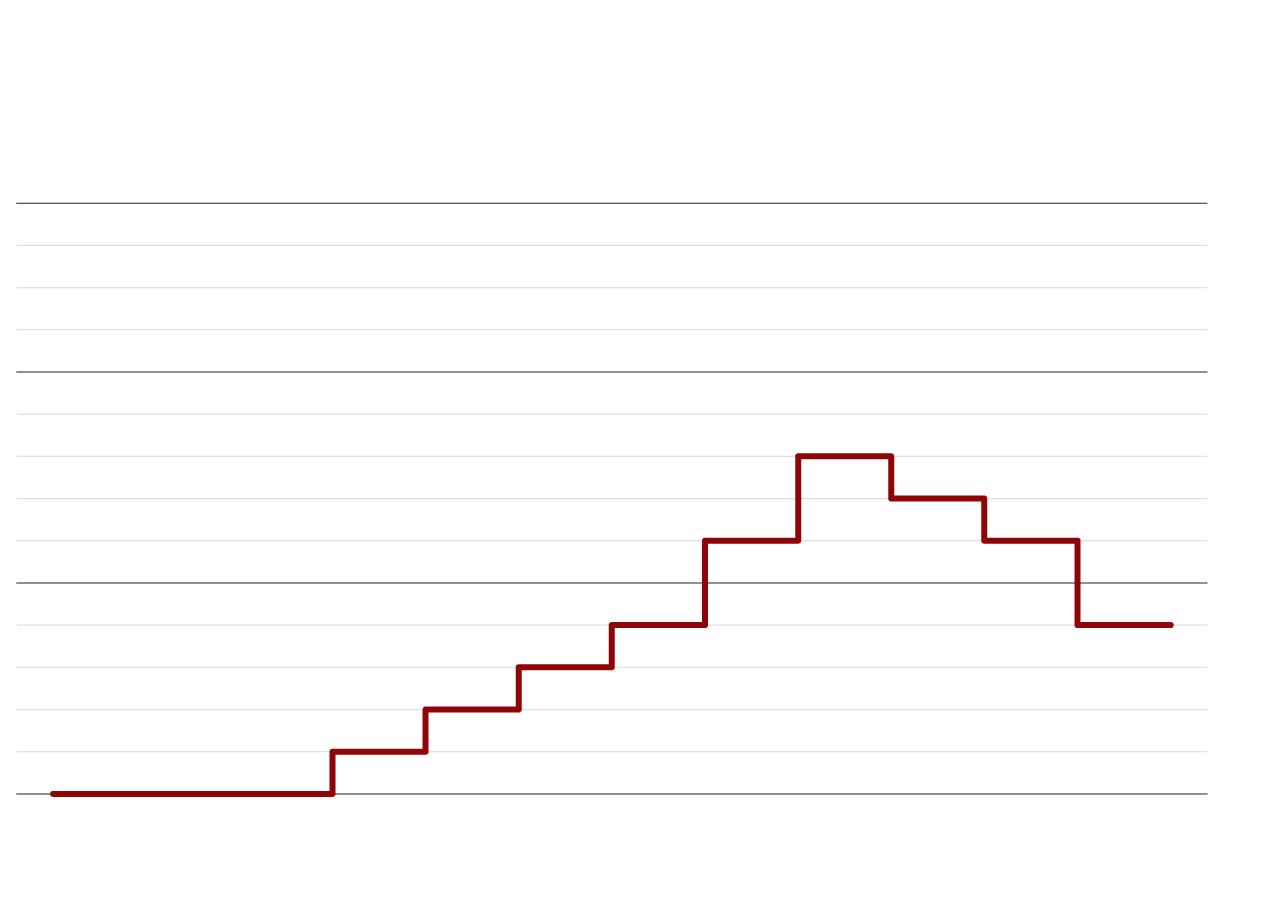

Russia’s position among

countries by number of

scholarly papers published

Source: Institute for Statistical Studies and Economics

of Knowledge

Russia’s position among countries by

number of scholarly papers published

Source: Institute for Statistical Studies and Economics of Knowledge

Russia’s position among countries by number of

scholarly papers published

Source: Institute for Statistical Studies and Economics of Knowledge

Many international exchange programs have been canceled — some because Russian students now have difficulty obtaining visas. Still, a heavy brain drain is underway. “All those who could — they left the country,” Skopin said of his students. “Those who can’t are thrashing around as if they are in a cage.”

Martin is among those who got out — he was recently accepted into a prestigious master’s program abroad and plans to continue his research into 19th-century Australian federalism.

Skopin now teaches in Berlin and is a member of Smolny Beyond Borders, an education program that seeks funding to cover the tuition of students who leave Russia because of their political views. As of late 2023, an estimated 700 students were enrolled.

[ad_2]

Source link